The day after the Fifth Patriarch erased Huineng’s poem from the wall, he quietly went to the kitchen by himself. He found Huineng there, milling rice with a heavy rock tied around his waist. This was necessary because Huineng was too thin and needed the extra weight to help him bear down on the rice.

The day after the Fifth Patriarch erased Huineng’s poem from the wall, he quietly went to the kitchen by himself. He found Huineng there, milling rice with a heavy rock tied around his waist. This was necessary because Huineng was too thin and needed the extra weight to help him bear down on the rice.

The Fifth Patriarch was impressed. Huineng’s dedication reminded him of those who were so devoted to dharmic studies that they disregarded and transcended physical limitations. He asked Huineng: “Is the rice ready?”

Huineng replied: “The rice has long been ready, and only needs to be sifted.”

This was what the Fifth Patriarch wanted to hear. He raised his staff, tapped the rice mill three times, and left.

Huineng understood his Master, even if their exchange might seem cryptic to someone else. He stayed up late, until the third watch of the night, and then he went to the Fifth Patriarch’s room — just as he was ordered.

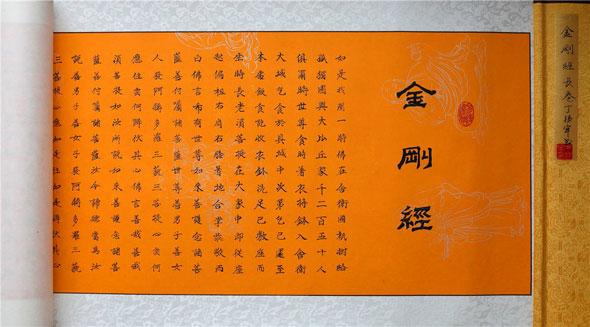

The Fifth Patriarch used his robes as cover, to shield them from view. Then, he taught the Diamond Sutra to Huineng. When they got to “one should be non-abiding, thus giving rise to one’s mind,” Huineng experienced a moment of great awakening.

In sudden realization, he said: “None of the myriad dharmas of the world is separate from the nature of the self!” Then, he turned to the Fifth Patriarch to exclaim:

“How unexpected that self-nature is originally clear and pure in itself! How unexpected that self-nature is originally not born or extinguished! How unexpected that self-nature is originally complete and sufficient in itself! How unexpected that self-nature is originally not moved or shaken! How unexpected that self-nature is able to produce all dharmas!”

Hearing this, the Fifth Patriarch knew Huineng had attained enlightenment. He nodded: “If you do not know your own mind, studying the dharma brings no benefit. If you do know the mind of the true self, then you will also see its true nature. This is how one becomes a person of honor, a heavenly teacher, and a Buddha.”

That night, without anyone knowing, the Fifth Patriarch passed his position onto Huineng. He said: “You are now the Sixth Patriarch. You must take care of yourself in order to relieve others of suffering. You must ensure the teaching will continue flowing through the generations. Do not ever let it come to an end.”

He pointed to the robe and the bowl: “Bodhidharma used these to symbolize our tradition, but they are not the dharma. True dharma is transmitted from mind to mind and for each person to experience within. This is how it has always been since ancient times, from one Buddha to the next. These items have become the focus of contention, so after I pass them on to you, do not pass them on to anyone else. Heed my words, or your life will be in danger. In fact, you should go now. There may be people who intend to harm you.”

As Huineng hurried to leave, he knew nothing would ever be the same again. It was hard to believe that the responsibility of the Sixth Patriarch now rested on his shoulders. His destiny was just beginning to unfold.

The Tao

The Fifth Patriarch could see in Huineng’s poem that he had a gift for metaphorical language, so he spoke indirectly. When he asked about the rice, he was really asking if Huineng was ready. Did Huineng have sufficient understanding of Buddha Nature, to take the next step of his spiritual journey?

Huineng understood perfectly and answered in the affirmative. He had been ready for quite some time. He understood what was required of him. He needed only the Master’s confirmation of his readiness.

Non-abidance is a key concept in the Diamond Sutra. To abide is to remain fixed or attached to a particular location or situation. To be non-abiding is to free oneself from such attachments, to realize that external circumstances and internal dispositions are ultimately illusory. Only with such freedom can the mind of one’s Buddha Nature arise.

This basic truth expanded Huineng’s horizons. Suddenly, he was able to grasp the essence of human nature like never before. We are not this crude substance that makes up the body. What we are is something that has always been and can never cease to be. Each of us is an engine of creation with unlimited potential. In your own divine essence, anything is possible.

The Fifth Patriarch’s final lesson for Huineng was the capstone of all his teachings. The vast majority of humanity remained fixated on material things in the material world. Thus, Bodhidharma’s robe and bowl were not only the symbol of authority in the Zen tradition, but also became objects to be lusted after and fought over. By the time of the Fifth Patriarch, the negative consequence of the latter outweighed the positive meaning of the former. This was why the practice of passing them from one generation to the next had to end. This became one of the Huineng’s tasks, to be completed in the future.

First, he had to save himself. Huineng needed to ensure his own survival in order to fulfill his mission. This was the unlikely and dramatic beginning of the Sixth Patriarch, and it all started with Huineng’s escape — away from the temple, ahead of pursuers — in the early hours of the morning.

- The Sad Lady - December 1, 2019

- Purchasing Yi - December 1, 2019

- The Seven Virtues of Water - August 21, 2018